The How To Be Project: Ten Plays for Racial Justice @ Bishop Arts Theatre Center

—Jan Farrington

Full of ideas and emotions, laughter and pain, the ten plays of The How to Be Project: Ten Plays for Racial Justice at Bishop Arts Theatre come at you one after another, crowding your mind and heart: quotes projected onscreen, one short drama coming fast after another, no time to do more than just go with it—and come out on the other side.

Bishop Arts asked ten Texas-born or Texas-based Black playwrights to think about Doctor Ibram X. Kendi’s book How to Be an Antiracist, and to write short works for the stage that were “in conversation” with his ideas. Among Kendi’s central thoughts is that it’s impossible to grow up in our society without being a racist in some way, internalizing racist ideas even as we protest we “don’t think that way.” And once recognizing that truth, our job is to find active ways to become “antiracist,” to do the work that will move us closer every day to the Beloved Community of Dr. King’s vision.

To begin with the most important information, the ten playwrights of the Project are: Kristen Adele Calhoun, Bwalya Chisanga, Zetra Goodlow, Michael Harrison, Oba William King, Eugene Lee, Alle Mims, Jonathan Norton, Paula Sanders, and Erin Malone Turner. The cast members, all performing multiple roles, are: Olivia Broome, Rjay Colbert, Jamal Dillard, Jon Garrard, Dillard Gibson, Shun Lauren, Alexandra Lofton, Octavia Y. Thomas, and Z.Z. Wright.

Will every one of these plays stand the test of time? Perhaps not. But without exception, all were interesting, and a few were terrific. Some will stay with me for a long time; I think Dr. Kendi would say they’re doing the work.

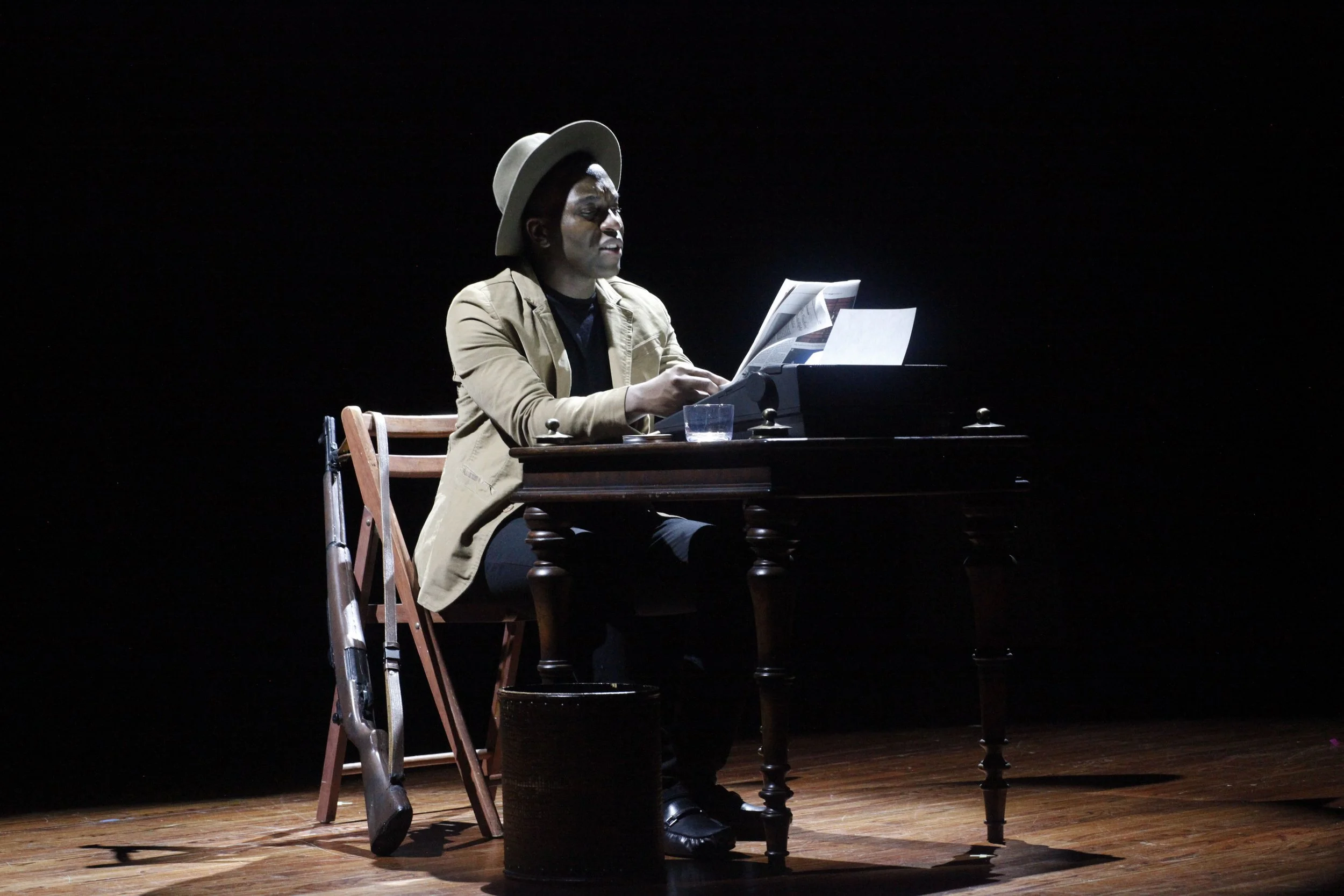

The show opens and closes with two storytellers, both played compellingly by actor Shun Lauren. In “Water Fountain 1967” Lauren is the playwright himself, Louisiana Creole storyteller Oba William King, who is recalling an episode of his childhood that involved a water fountain, a hose on the ground, and a little boy new in town who didn’t know the rules. Anyone over a certain age who grew up in Texas or the Deep South will know where this story’s going—but you’d be surprised. King, a vivid and wise wordspinner, gives the tale a twist that isn’t a happy ending, exactly, but a hopeful one.

At the end of the show, Lauren plays the great dramatist August Wilson, walking us through a public quarrel he had with a white theater critic, Robert Brustein, who also had his own theater company. Their battle is a hard one to sort out—you’re on Wilson’s side, but see some value in the other man’s thinking (though you may doubt his good intentions). This is hot playwright Jonathan Norton’s contribution, a kind of inside baseball for theater junkies (raise your hand). It’s hilarious, and the title alone is spit-take funny. I won’t give it away.

In between these bookends the stage is crowded full of energy, heart, and thought. Paula Sanders’ play “Classes” is a battle of three women for the soul of a young doctor (Lauren). Will he follow his fiancée (Wright) out of his community and into the Good Life, or stick with his mother (Thomas) and friend (Lofton), who hope he’ll put his education to work in the old neighborhood? In Eugene Lee’s “Government Cheese,” Thomas is searing as a Black mother who raises her kids by the rules of “ah-similating”—on government-issue cheese and canned meat. “Made in America…for whatever America needs them to do.”

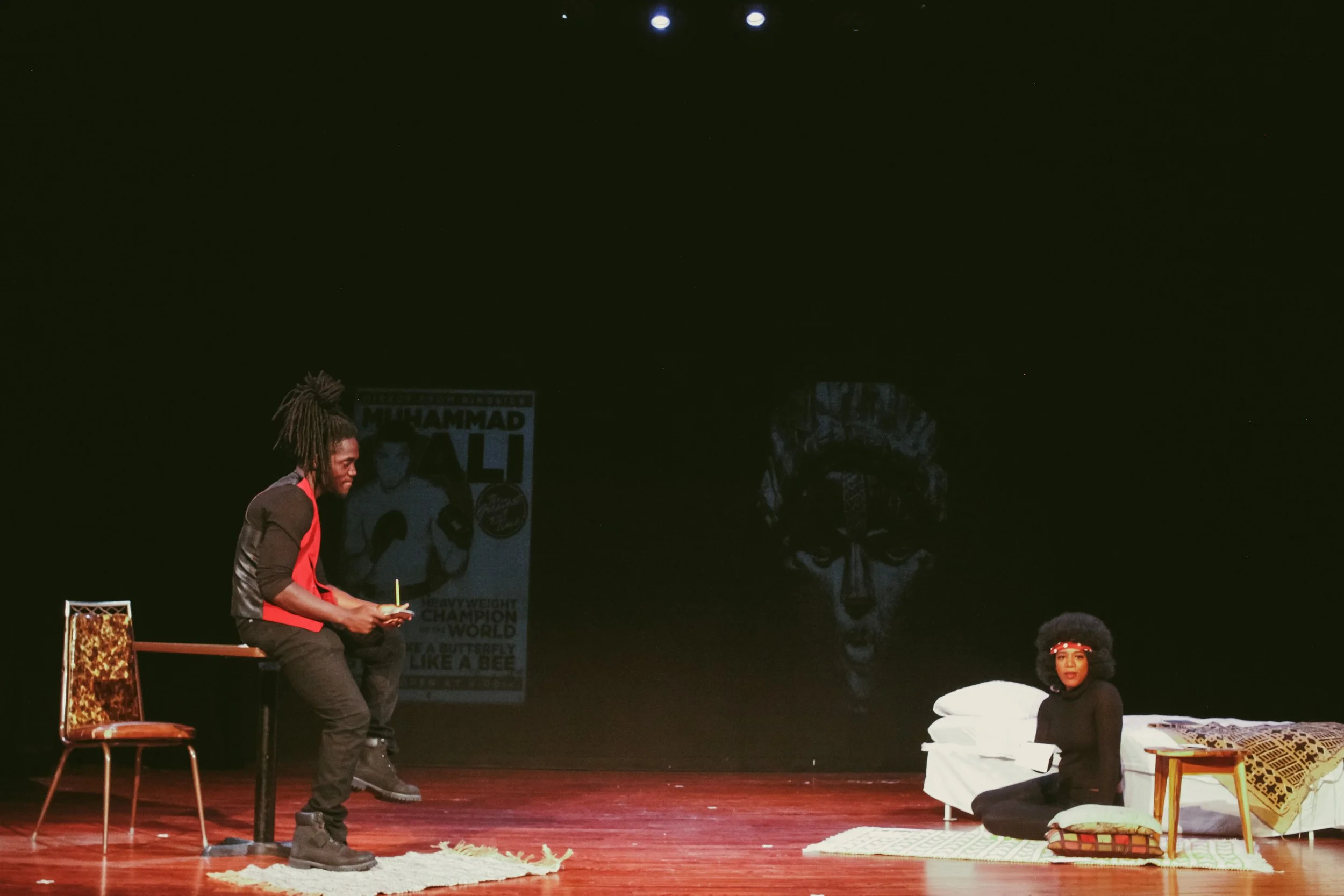

Calhoun’s short, sweet “What Would Have Been” gives Wright and Gibson a chance to play warm-hearted lovers, writing letters that move the plot while they’re apart. It all seems to go well—but still, that title brings a shiver. Is this story only a dream? Olivia Broome is the teacher you shake your head about in Bwalya Chisanga’s “Self Education,” a frustrating story of a student (Lofton) whose imagination and work keep running aground on “the rules” of school. Erin Malone Turner’s “Gray” is a chilling look ahead to a world after “the race war,” and Zetra Goodlow’s “The Elephant in the Room” makes visual the omni-presence of race in a surrealistic style. Michael Harrison’s “The Ghost of History” was edged with sadness, funneling down to a stark final line: “We can’t get married.” And Alle Mims’ “A Good Neighborhood” is every parent’s fear—of doing the right thing, and having it go wrong.

David Saldivar’s fight choreography is on good display, as is the talent of choreographer Jasmine Mychell Miller. Adam Chamberlin and Joshua Nguyen (on lights and sound) give polish and energy to the proceedings. And last but most certainly not least, director Morgana Wilborn pulls really fine performances from her young cast. I’ll be looking to see these actors again.

And (not that they asked) if I were Bishop Arts, I’d think about doing this again next year.

WHEN: Through March 6

WHERE: Bishop Arts Theatre, Oak Cliff