Corsicana @ Playwrights Horizons, New York City

—Kate Farrington

Photo Credit : Julieta Cervantes

It doesn’t matter that I’ve lived half my life in New York. Any time a play (or playwright) with Texas roots finds its way to NYC, I feel a sort of “home team” excitement. I go into such shows eager for a glimpse of home.

Corsicana, Will Arbery’s deceptively quiet study of grief, love, and community, conjured a very particular memory. As an uncomfortable Lot begins to tell Ginny the story of his mother’s death, he quickly swerves into a ghost story with origins stretching back to the wilds of 19th century frontier life. Then he yanks the tale out of the human realm entirely, declaring Texas to be haunted by the ghosts of dinosaurs—dinosaurs who can’t leave, and who grow wiser and sadder the longer they stay.

Sitting in Playwrights Horizons, I flashed to a childhood trip to Dinosaur Valley State Park near Glen Rose. Slipping off my purple jelly sandal. Planting my bare foot inside a huge dinosaur footprint. Small human girl meeting—touching—prehistoric giant. The memory came and went in an instant, but in full technicolor.

The dinosaur reference hit me for two reasons. (Okay, three—you don’t get a lot of dino-ghost shout outs.)

First, of all the symbols in Corsicana that touch on how past/present/future intertwine, this one points most directly to the expansive scale this intimate play artfully invokes. We are witnessing a small story with cosmic reach.

Second, Corsicana is nothing if not a story of excavation. Personal, intimate discoveries that, when brought into the unsparing light of the present, continually reposition what we understand about this messy, struggling group of people. History shaping the present.

Arbery’s Pulitzer-nominated Heroes of the Fourth Turning, which premiered at Playwrights Horizons in 2019, introduced a backyard of ferocious conservative Catholics battering away at liberal secularism in a dark, wild setting. By contrast, Corsicana takes us to a small (ish) Texas town where an eclectic, fragile foursome just tries to get from one day to the next. But if Corsicana lacks the verbal pyrotechnics of Heroes, its idiosyncratic humor and languorous portrayal of grief is almost a guided mediation.

Adult siblings Christopher and Ginny have recently lost their mother, and neither is dealing well with the loss. Christopher has returned to Corsicana to care for thirty-something Ginny, who has Down syndrome. But he himself has sunk into apathy, relying on Justice, their mother’s close friend, to pick up groceries and sometimes stay with Ginny (NOT to babysit her, Ginny angrily asserts). Meanwhile Ginny, once deeply involved in her church choir and volunteer work, watches endless Disney Channel reruns, and refuses to connect with former friends.

Simply put, they’re stuck. Unwilling to confront their pasts, they can’t move forward. Identical back-to back living rooms and stark lighting (by scenic designers Laura Jellinek and Cate McCrea, and lighting designer Isabella Byrd) subtly reflect this inertia. Sitting on a turntable, the nondescript room spins—to reveal an identical nondescript room. Nothing here is changing.

Somewhat hypocritically, Christopher wants his sister to unpack what she’s feeling, but all Ginny offers is “I can’t find my heart.” In a last-ditch attempt to reach her, Christopher approaches Lot, a reclusive local artist, for a favor. Would Lot work with Ginny to write a song? Despite misgivings about working with someone “special” (an uncomfortable word that accumulates shades and nuances as the play progresses), Lot agrees to give it a go.

The fallout of Ginny and Lot’s awkward, cautious interactions form the loose spine of Corsicana, forcing all four characters to confront aspects of their experiences and personalities that disturb them, that call into question the identities they’ve built for themselves or been forced to assume by others.

And in the process of this emotional excavation, this reshuffling of the self, they and we discover an entire reality beyond the visible world. The anonymous trappings of a house that feels temporary at best and preternaturally hostile at worst (what’s up with the Wi-Fi?!?) exist in direct opposition to an equally important and never-shown reality. Ginny sings and dances in her room when no one else is watching. Lot creates artistic masterpieces he’s reluctant to share. Justice keeps seeing (dreaming?) a shadowy but not malevolent figure around town. And Christopher clings to a life-altering letter we never see.

In envisioning the invisible, we find that these worlds are no less real. It is in these hidden (from us) spaces that the characters find hope—where they live, as Justice puts it, in “expectation” that things can still get better. But that can only happen if the inhabitants of Corsicana are brave enough not to stay mired in grief—a decision which must be made and then made again. And again.

Arbery’s play sets its own gently bittersweet tone and moves at its own measured pace, which could easily in the wrong hands come across as meandering. But the playwright’s willingness to give his characters the space and time they need to evolve feels vital to the story being told. And director Sam Gold wisely lets them get on with it—the staging is as expressively sparse as the language is dense.

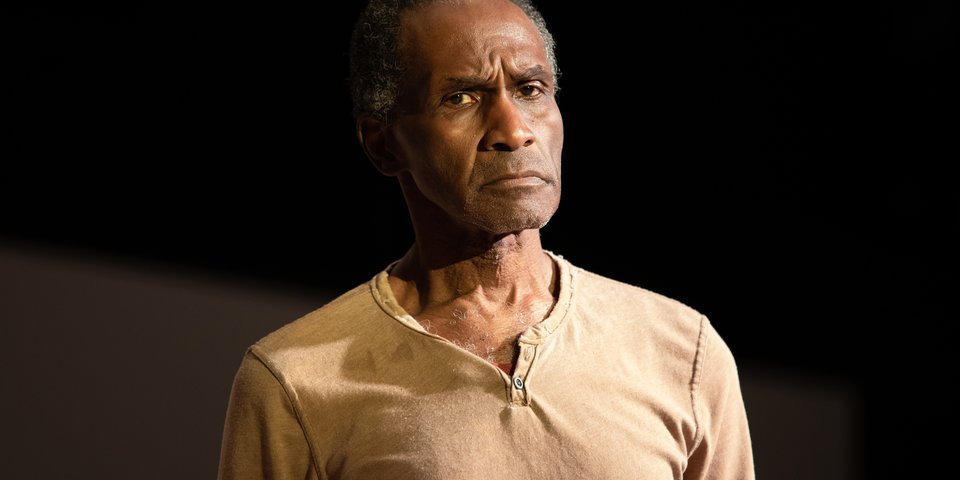

Recent Tony award winner (for Dana H.) Deirdre O’Connell gives a powerful, tumultuous performance as Justice, a study in chaotic goodness. Acting with the best intentions, she comes to recognize the mess her fears and selfishness can leave behind. In an exquisitely understated performance, Harold Surratt’s troubled Lot is the perfect partner for O’Connell’s Justice—his deadpan delivery and laconic insights the perfect foil for her endless rush of passions and words.

As the brother, Will Dagger offers a performance that grows richer as the character unfolds. Once Christopher allows himself to fully recognize his past and present trauma, his outlines and contours become beautifully clear. His Act II story of coming face-to-face (almost mystically) with his teenage self is a masterpiece of tragedy tempered by gentle humor.

Jamie Brewer’s Ginny is superbly mercurial. Moving from teasing to frustrated, brutally honest to nurturing, often in the span of a few lines, Brewer captures the complex emotional life of a young woman whose plans and desires sometimes throw others for a loop. The play cannily articulates the difference between the “needs” neurotypical people are comfortable allowing Ginny to have, and her expressed “wants”—which they too often and too easily dismiss.

Corsicana asks us to accept that the space-time continuum is just a bit fluid, with What Was, What Is, and What Will Be existing in a sort of triple exposure. Somehow it is exactly this willingness (by both playwright and characters) to step outside the confines of linear time and visible reality that make the play seem larger than its story. By the time we hear the song that Lot and Ginny have created (after much travail), there is a strange sense we have unexpectedly stumbled onto sacred ground.

But the Wi-Fi still sucks.