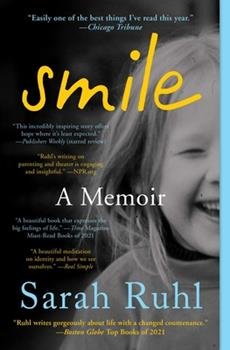

Smile: The Story of a Face by Sara Ruhl

—Jan Farrington

Smile: The Story of a Face, by Sarah Ruhl

(Simon & Schuster, 2021)

“When the face is a mask, the soul hides or relocates.

I am trying to welcome my soul back into my face.”

When playwright Sarah Ruhl (Stage Kiss, Eurydice, The Clean House, Orlando) gave birth to twins in 2009 (a boy and girl; she and her husband already were raising a toddler), it had been quite a year. Her first play on Broadway (In the Next Room: or the vibrator play) was a hit; she remembers feeling hungry and happy as she held the twins. The next day, a hospital worker noticed her eye looked “droopy.” Ruhl had Bell’s palsy, not uncommon for new moms. Mostly, it goes away in a few weeks or months, this one-sided “frozen face.”

But Ruhl’s did not.

Her book Smile: The Story of a Face is a memoir of the next decade or so of her life: as a woman, a mother, a wife, a working artist, and a patient. Complicated? Oh, my. And though Ruhl experiences “plenty of joy” during those years—and comes to see what’s happened not as a tragedy but a “disappointment”—it changes her world, and her outlook on such disparite things as symmetry, her Catholic and Buddhist God(s), men who ask women to smile, and the reality of postpartum depression.

So many questions. Does a smile create happiness, or is it there even if your face can’t express it? Will her children be traumatized by her “still face” and inability to give them a natural smile? Will actors in rehearsal be thrown off by how she’s responding (or not) to their performances? Over time, Ruhl tries lots of doctors (wonderful and awful), therapies, facial exercises, acupuncture—and theatrical techniques too, including mime training and the Alexander Technique.

Along the way, she writes about her growing children, her loving, complex relationship to her late father, and her marriage to psychiatrist Tony. In a comment about the book, actress Mary Louise Parker, who starred in Ruhl’s 2008 play Dead Man’s Cell Phone, writes: “I’m now accustomed to Sarah’s whipping out profound and necessary books that I can’t put down even when I smell dinner burning, but I guess I wasn’t prepared for her book about Bell’s palsy to provide some of the most deeply romantic passages about married love I have ever read….I adore this book."

All I can say is: I’m glad I read Smile—and want to let Sarah Ruhl have the last word.

“My years of writing plays,” she notes, “tell me that a story requires an apotheosis, a sudden transformation. But my story has been so slow….A woman slowly gets better. What kind of story is that?” But from the experience, Ruhl learned something she’d always known about art, but not life: that imperfections and messiness have “the power to open the heart.” And she found the answer to her early question about whether her “frozen” face would make her children love her less.

“Anna [Ruhl’s older daughter]…said: ‘I always thought of your face as a beautiful house. A wall suddenly fell down, and you tried to rebuild it, brick by brick. And you couldn’t quite. And all you saw was the wall. But all we saw was our house.’”