‘Bitter Crop: The Heartache and Triumph of Billie Holiday’s Last Year’

—Cathy Ritchie

Bitter Crop: The Heartache and Triumph of Billie Holiday’s Last Year

By Paul Alexander (Knopf, 2024)

True confession: I have never cared for Billie Holiday’s singing. But as a biography nerd, I’ve always been affected by the tumultuous history behind her personal and professional lives. Fortunately, Holiday continues to inspire the world via film, compilation recordings, and books. And speaking of the print medium, I offer an enthusiastic recommendation of the latest such Holiday remembrance: Bitter Crop by Paul Alexander.

It’s outstanding.

Holiday died in July 1959 at age 44. While Alexander’s chronology sways to and fro a bit, he basically gives readers a month-by-month account of her final days, beginning in June 1958 and concluding with her funeral almost exactly a year later. These weeks were indeed difficult for Holiday, though the release of her 1958 album Lady in Satin would be arguably the final shining moment of her career.

Nevertheless, multiple issues weighed heavily on the singer. Her health declined steadily during this period, the primary cause her advanced cirrhosis of the liver. In addition, Holiday still could not perform in any New York City nightclubs that served liquor, as she no longer had a valid “cabaret card”—a result of her 1947 arrest for narcotics possession. Caught in this bureaucratic nightmare, Holiday could perform only outside the New York area. The venues were less than glittering, the pay low. As her financial circumstances worsened, she also was also trying to cope with a messy divorce from her third husband, Louis McKay. (They married in 1957.)

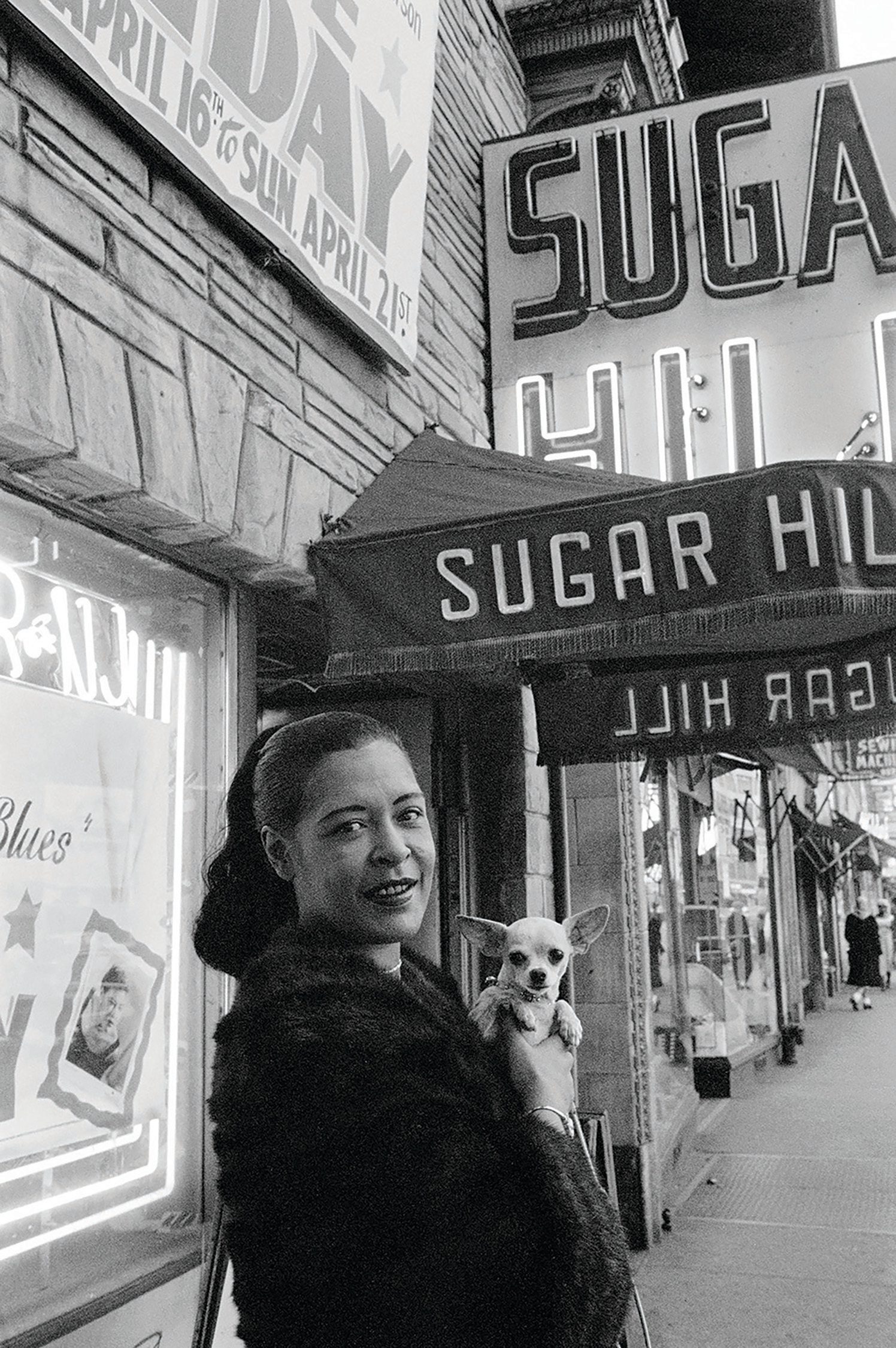

Alexander vividly depicts Holiday’s ongoing ordeals, but offers readers much more. He masterfully travels between the months of his primary focus and stages of Holiday’s earlier life, including her traumatic childhood and young adult years. She reached the peak of her success and acclaim in the late 1930s-1940s, a time period that encompassed her controversial association with the vivid anti-lynching song “Strange Fruit.” Alexander’s writing style is consistently smooth and engrossing.

Another reader bonus: the author skillfully immerses us in the world and ambience surrounding Holiday's career, giving us portraits of the many musicians who became her colleagues and friends. Readers experience her daily life in the world of jazz and blues.

To be sure, Alexander is forthright about Holiday’s failings, especially her tendency to distort facts about herself all the way to (and including) outright lying. Her purported 1956 autobiography Lady Sings the Blues is a prime example. A journalist friend served as her co-author, but it’s since become a truism that most of Holiday’s recollections were exaggerated or total fabrications.

And while many accounts of Holiday’s life emphasize her drug abuse, she ultimately died of alcoholism. Her heroin use was comparatively sporadic, but she never stopped drinking, despite her doctors’ pleading and some scattershot efforts on her part to become sober.

Alexander shares some touching personal anecdotes about Holiday. Throughout her adult years, she longed for children, but the tenuous state of her marital relationships made that an unlikely possibility. She compensated by becoming a godmother to many of her musician friends’ children, and reportedly went out of her way to relate to any young people who crossed her path.

For me, the most moving revelation in the book concerns Holiday’s unique early-1950s relationship with actress Tallulah Bankhead. The two began as friends, but eventually became romantically involved. Alexander—and the few who knew about the women’s love affair at the time—contend that it was one of the most positive and nurturing relationships Holiday ever experienced.

Yet for reasons unknown, and which Alexander does not reveal, Bankhead and Holiday suddenly parted ways even as friends, a loss that reportedly haunted the singer until her death. Holiday had numerous caring people in her life, but her final years found her without the ongoing comfort of a devoted partner. Alexander theorizes that Bankhead could have been that person for her, but their time ran out.

Holiday’s death in July 1959 made headlines around the world. It inspired some tsk-tsking commentary about her drug use, but many of her fellow music makers were devastated; Frank Sinatra reportedly mourned her in solitude for days.

Though many jazz aficionados immediately acknowledged her greatness and legacy, Alexander concludes: “Over time, in various forms of media, Billie Holiday was portrayed as a drug-addicted victim who happened to sing, even as her contribution to American culture was downplayed or ignored. But a more suitable assessment of her would result from viewing her as she was—an iconoclastic artist who made a timeless contribution to American art in the tradition of innovators like Walt Whitman or Georgia O’Keeffe or Aaron Copland or D.W. Griffith. She has earned her place as a figure afforded reverence and admiration in the continuing American story.”

Bitter Crop is an outstanding addition to the music biography genre, and will help guarantee that the glow of Lady Day’s achievements will never fade.