AWAKE @ Bruce Wood Dance

Photos by Sharen Bradford/The Dancing Image

—Gregory Sullivan Isaacs

Bruce Wood Dance presented AWAKE this weekend—a dramatic program of four dances (and one dance film) at Moody Performance Hall in the Dallas Arts District. I attended the first of the company’s three performances (on Friday evening); the program was a thought-provoking display of some brilliant dancing, as well as a showcase of choreographic influences handed down from mentor to student. AWAKE explored different media for dance and addressed subjects that are both timeless and current.

Since the dances were so completely different, perhaps it is best to start out with a discussion of the related contrasts.

The messages that the dances explored were both subtle and painfully obvious, and the effect on the audience was more significant than any of us anticipated. The dances were beautiful, ugly, harsh, graceful, angular, loose, interactive, and isolating. Historic ballet steps contrasted with current street hip-hop. Explosive vocalizations occurred when the movement made it logical, but also at other moments when such a stress grunt was jarring. When moving as a tightly unified corps de ballet, some rebel dancers would break off in a frantic manner. Pairs would gently merge and then part ways, while others indulged in erotic grappling. Gender was fluid in some of the dances, while the difficulties of male-female bonding were the crux of others

What was consistent throughout was the stunning technical excellence of the dancers and the brilliant choreography they were given to dance. This combination of excellence—given, received, and performed—made for an exceptional evening of dance combined with sometimes disturbing social commentary.

And Lar Lubovitch was in attendance.

That simple sentence doesn’t begin to convey what an occasion this was. Lubovitch is one of the greatest choreographers in the history of modern dance. And, here he was! An even greater Lar-ish connection is that Bruce Wood got his start in Lubovitch’s dance company. He absorbed Lubovitch’s innovations, pushed them through his unique filter, and incorporated elements into his own choreographic voice.

Lubovitch’s personal influences were many. He started off as one of what we then called “go-go” boys (and it’s reported that he was terrific). His “actual” teachers were Martha Graham, Alvin Ailey, José Limón, and the British choreographer Antony Tudor. All giants, but he credits Tudor for teaching him the symbiosis between movement and music.

Dvořák Serenade, a 2007 ballet by Lubovitch, opened the evening’s program. It is set to several movements of Antonín Dvořák’s lyrical and expansive Serenade in E Major.

Lubovitch’s work is a gentle, flowing dance with motions that feel deliberate at times, or flow in such a manner that one might think the dancer's bones have melted, or their limbs gone floppy. They are dressed in white gossamer garments that breezily move with the dancer’s gentle movements. Joyful and rhapsodic movements contrast with more forceful ones. I was reminded of the ancient Taoist practice of Tai Chi, in which slow controlled movements can impart great strength.

There was one startling moment. Lubovitch insisted that the company begin the dance over, from the top. Apparently, the lighting cues were off and this affected the look of the work. The audience didn’t appear to have noticed the “glitch”—but none of us minded seeing some of the ballet again.

A work by Bruce Wood titled Our Last Lost Chance took Lubovitch’s gentle world and brought it into our complex, sharp-elbowed, and hostile one. Wood retained some of the grace, but provided contrast with jerky motions, odd lifts (with the partner upside down), and couples who entwined with a physicality that was compelling but lacked eroticism. Dancers Stephanie Godsave and Alex Brown were featured. Musically, this very modern work is set to an eclectic soundscape from composer Olafur Arnalds and several others that seemed to span the ages.

An intriguing dance film titled Promise Me You’ll Sing My Song followed. It was choreographed by Adam W. McKinney and created on film by The Digibees. This piece focuses on the story of the 1874 lynching of Reuben Johnson, a Black man, near Mountain Creek Lake southwest of Dallas. We don’t see this horrific event, but dancer Matthew Roberts expresses the atmosphere in which it happened. Singer-songwriter Najeeb Sabour’s score features a mournful cello to create deeply melancholic music.

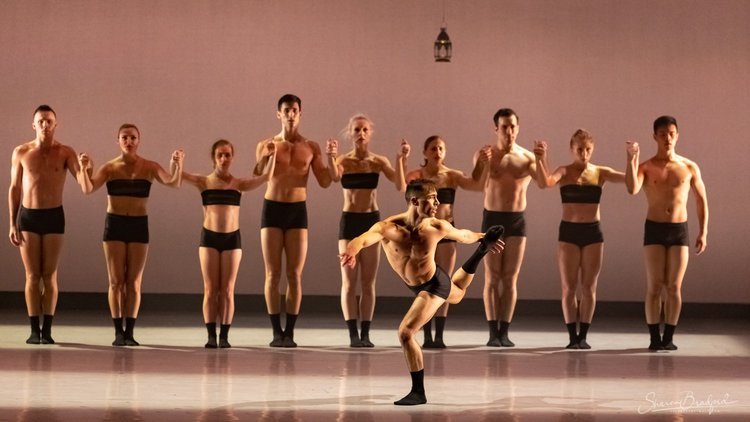

The final work on the program was Forbidden Paths, created by choreographer Garrett Smith in 2019. As opposed to the other works, Smith’s dance explores restrictive societies where dancing, and even human contact, is banned. To a diverse and percussion-heavy Middle Eastern-influenced score, Smith turns even a casual inter-human touch into a powerful and disabling electric shock. But in face of this impediment, he portrays the desire for contact as an irresistible force, no matter the consequences.

This troubling but energetic work brought the program to an exciting close. The ovation that followed was filled with much loud cheering, mixed with well-deserved, appreciative applause.

WEB: brucewooddance.org (watch for upcoming events early next year, including the company performing at the Dallas Spring Arts Festival, April 8 @ Klyde Warren Park, and at the 13th Anniversary Performance + Gala, April 29)